Sanso Moderno: A Brilliant Summer for Life’s Autumn by Reuben Ramas Cañete, PhD

“What is apparent, and most critics make a point of this, is poetry. The definition of a poem as ‘…a rhythmical composition…expressing facts, ideas, or emotions in a style more concentrated, imaginative, and powerful than that of ordinary speech…’ seems appropriate to the qualities in Sanso. A look at Sanso’s art immediately draws admiration for his mastery of technique. The authoritative brush strokes, the intricacy of detail, the tapestry of complex textures, the credibility of his imagery, are what first provoke the viewer’s attention. But even as one marvels at the technique and the manual skill—as one is pulled into the picture, the viewer is instantly conscious that there is more than dexterity in the work. Identifying this content as poetry satisfies most viewers…”

Alfredo Roces, 1976.

Spring

One of the precious members of that extraordinary batch of UP Fine Arts students who first entered the Diliman campusafter the Liberation, Juvenal “Juvy” Sanso survived the horrors of World War II and, along with classmates like National Artist Napoleon Abueva, Angel Cacnio, Araceli Limcaco (nee Dans), Rodolfo Ragodon, Pitoy Moreno, Larry Alcala, and underclassmen National artist Jose Joya and National Artist Federico Aguilar Alcuaz, blazed a unique trail for generations of Filipino artists to follow in the suceeding decades. Often mentioned as the “Modernist Batch,” this group would build upon the advocacy for new-ness, relevance to contemporary society, and the search for unique forms of artistic expression started by Victorio Edades in the late Twenties. During that time, UP Fine Arts was still dominated by Conservative academicians like Guillermo Tolentino, Fernando Amorsolo, Dominador Castañeda, and Toribio Herrera, who idealized the classic if by then atrophied formulas of proper proportion, beauty, and the notion of perfection in the depiction of nature and the human body, traits that were increasingly felt to be irrelevant following the brutal destruction of the war and the championing of Modernism by the United States and the Western world as the artistic style for the free world.

This reversal of artistic winds, exemplified by the August 8, 1949 feature article on Jackson Pollock by Life Magazine, which asked the rhetorical question: “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?,” was rooted in the deeper ideological conflict between capitalism’s advocacy of the free market of goods and ideas, versus communism’s planned central economy and rigid obedience to the Party. The varied, often unpredictable permutations of various Modernist art styles, from the grids and planes of Piet Mondrian, to the exploding cubistic compositions of Picasso, or the mystical color and line abstractions of Kandinsky, were all felt to be freer and in tune with the ideals of liberal democracy and laissez-faire business. This was in direct contrast with social realism, which was valorized by socialist states as the only authentic aesthetic style “of the people.” One can see this in the explosive birth of Modernist and abstract art movements across Europe and Asia after World War II, from COBRA and Art Informel to the Gutai Group. In the Philippines, this was exemplified by the Neo-Realists, which coalesced around the Philippine Art Gallery of Lyd Arguilla in the early Fifties.

The period between the late Forties to the early Fifties was thus a highly fertile time for artistic imagination and individuality to grow. More so since the Philippines was painfully rebuilding from the devastation of war while enduring a raging pro-communist insurgency in the countryside led by the Hukbalahap. The country was reeling from the heady effects of independence, although official corruption and public accountability had already began its ceaseless battle within the Philippine bureaucracy. In this unlikely atmosphere, the twin cornerstones of American post-war policy in the Philippines namely pushing economic development on the one hand, and military aid with extensive counter-insurgency operations on the other, made the Philippines a more stable country enjoying a high rate of economic growth, albeit supported heavily by subsidies. The country also supported art that was in tune to America’s own vision as the cultural heartland of the free world.

Like his classmates, Sanso learned the basics of traditional genre painting from his UP mentors, augmented as it were by tutorial lessons he first took under Alejandro Celis. The social misery around him, and the global pessimism of the nuclear arms race and the Cold War in the early Fifties, however, also made Sanso sensitive to the depiction of reality as perceived in his surroundings. An enterprising Postwar bus conductor, Sanso had a front view scene of the miasma of outcasts, beggars, and vagabonds that prowled Manila’s streets. This he immortalized in two early works, The Sorcerer (1951) and Incubus (1952). Inaugurating his “Black Period” works, these would point the way to a whole series of semi-abstracted and Expressionist paintings that Sanso did in his European sojourn from 1952-1958.

The Black Period was a means of graphically working out Sanso’s traumas of the War, firstly in Rome, and finally Paris, where he enrolled at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts. Grotesque faces, skulls, and screaming heads in black were cobbled together into surreal bouquets in still life, as well as depictions of urban sidewalks and markets that were seemingly populated by monsters. One such example from this period is Baudelarian Image, where the depiction of an otherwise normal Parisian lady is highlighted by the dark fright shock of hair, and large toad-like eyes that fretfully glance forward. Another example is Baudelairian Nightmare, a swirl of black ink that combine floral motifs and decapitated heads into a black bouquet, perhaps Sanso’s visualization of the 19th Century French critic Charles Baudelaire’s wickedly written Les Fleurs du Mal. This would climax in works like Flowered Skull, a study in black, blue, and white of a group of expressionistic flowers that decorate a human skull, a headful of floral hair that sardonically marks human existence as both fleeting and mysterious. The result of an encouragement by his printmaking mentor at the École Nationale, Edouard Georg, Sanso’s Black Period still lifes connected to the older European artistic tradition of the memento mori, the Renaissance Period’s moralistic meditation of the fleeting nature of life by including a human skull within an arrangement of flowers, food, and various musical instruments on a table. It is also a philosophical musing of the term natur morte (from where the word “still life” comes from), that once upon a time literally meant to depict dead plants and animals on a table (like those found in the works of the Dutch Baroque master Franz Snyders).

This dark spell was finally broken with his friendship to Agnes Rouault (daughter of Fauvist Georges Rouault) and Yves Ledantec, who graciously allowed him to room over during summers at their home at the Brittany coastline north of Paris. Musing on the rocky coastline with its tidal pools and marshes, Sanso found a lifetime of inspiration in this serene environment, with its pale sun or glowing moon. Later, he mingles this with Philippine scenes which he captured in his frequent vacations, such as baklad fish traps in Parañaque, or the barung-barongs of Manila and surrounding towns. This he expanded upon from 1958 to the Sixties and indeed until today these dreamy landscapes—and their poetically surreal still life equivalents—forms a large part of his artistic oeuvre.

One such work that characterizes this transitional period from darkness to light is Bridal Bouquet, a romantically tinged blue, green, and red depiction of a bouquet of flowers stripped of the hideous faces and gaping skulls that characterized the artist’s earlier bouquets, and replaced with abstracted forms that arises out of Sanso’s famously inventive techniques of texturization and layered process of painting. Another work that continues the use of black ink, but removes much of its previous foreboding, is Completed Light. A depiction of a group of houses with stilt legs floating over an ink-blackened estuary, this work from the 1960s marks the dual character of Juvy Sanso’s works: while they depict a social environment that is less than materially ideal, they nonetheless evoke a sense of wonder and mystery by the subject, refusing a one-dimensional commentary on the current state of human affairs by looking at the poetic nature of existence as a fleeting state of affairs that define the mortality of human life, in which one’s significant role is to be equally imaginative as well as active. This is then multiplied and varied with the endless energy and enthusiasm that Sanso has traditionally invested on his work, such as in Seaward, where a group of rowboats and fishing gear clump towards the center of the composition like a darkened hull-encrusted colony.

In a 1966 review of Sanso’s exhibition, the art critic Emmanuel Torres writes: “He can draw in a precisely realist manner without using the clichés and various devices of emotional blackmail (sentimentality, grandiose posturing, etc.) of so-called conservative artists. A firm, stoic intelligence controls Sanso’s line and color: a poetic sensibility baptizes the sensuous shapes of his flora and fauna with a strangely wondrous and solitary atmosphere; and imagination so exuberant it seems unlikely to suffer from boredom, exalts the most banal subjects like bottles, shanties, fruitstalls, picket fences and billboard signs to the level of heightened awareness, lyric wonder.”

These poetic surrealist landscapes from the 1960s ad 1970s can best be exemplified by works such as The Blaze of Growth, where layers of rocky coastline combines with the dawn-tinged scarlet of the rising sun with its fiery reflection on the water, a solitary ship’s mast in the center the only indication of human habitation in the landscape.

In a more recent article I wrote during his 2002 exhibition, I noted that: “The singularity of the style, with its variations of form, can be traced to a specific personality of the maker, and not how he pleases the audience by just putting pretty colors and ideas on canvas. The almost classical discipline of sticking to the subject matter with fanatical devotion is an indicator of how far Sanso has gone as a painter dedicated to his craft, without fear of public rejection or critical scrutiny. We can see a slight difference in his works, though, as if Sanso is already summing up his painterly life: landscapes with a ‘soft focus’ effect, done by repeated glazing that creates a mystical orange lighting, as if seeing beached coral beds in volcanic twilight; and still lifes with a ‘hard focus’ crispiness that brings out the sharpness of abstracted floral details versus green foliage and blue background.”

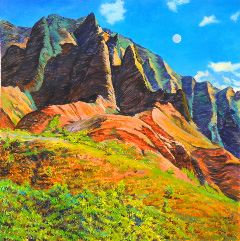

One can see this in such works as A Glow of Dawn, which harks back to a darker sensibility of Sanso’s Black Period, lifted from its shadows by the depiction of silent ruins in a red dawn. In Horizon of Grandeur, red cliffs and sand dunes that may have been located in Australia or Mars are marked by a somnolent moon and a misty blue sky, a reaffirmation of the poetic quality of vision that Alfredo Roces located in Sanso’s work in the 1970s. In By the Riverbank, Sanso perfects his method of layering textured patterns, colors, and overpainting into a compact but nonetheless breathy process of composition, setting horizontal layers of vertical and diagonal textures into imaginary beds of green and yellow reeds and thrushes that line riverbanks of a dreamy landscape, anchored by rocks that show beneath crystal-clear waves of blue water. A faint white celestial body, perhaps a winter sun or an autumn moon, balances the composition at the far background, producing a fairy-like lightness and natural mystery that is broken only by the bundled reeds at center ground that makes up a gated levee.

One must also reckon with Sanso’s equally prolific Modernist works in stage design (for the French operas Beatris and Wozzeck), textile design (for Balenciaga), and even experiments in photography as proof of his limitless ability to translate an aesthetic into any medium, bearing in mind that the material is simply a takeoff into the direction that the artist wishes to explore in terms of the interrelation between form and color. This exploration is more rightly than not infused with a brilliant coloration that has come to dominate Sanso’s “Poetic Surrealism” Period (1960-1984), which lifts the veil from his melancholy of the Black Period, and yet focuses this vision into worlds that appear both magical and real, mystical and visionary. The public enthusiasm for his works since the late Fifties is not in any doubt. Sanso’s works can be found in the collections of over 40 museums in the world, including the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the San Francisco Museum, The Art Institute of Chicago, The Cleveland Museum of Art, the Smithsonian Institute, the Museum d’ Arte Moderne in Paris, the Rosenwald National Gallery of Washington, and the Cultural Center of the Philippines. His collectors include the Rothschild Family, Nelson Rockefeller, Vincent Price, Elsa Schiaperelli, Jean Cocteau and many prominent, American, European and prominent Filipino families, particularly the Sy family who are his greatest local patrons.

Along the way, Sanso has also reaped the adulations and honors that could be bestowed to such a polymath of art. He started reaping awards early, starting from winning in the same year (1951) the First Prize in Painting (“The Sorcerer”) and First Prize in Watercolor (“The Incubus”) at the 4th AAP Annual Art Competition, Sanso has been awarded the King’s Cross of Isabella from the King of Spain, the Order of Chevalier from the French Government and the Presidential Medal of Merit from the President of the Republic of the Philippines. His exhibition record is also distinguished as it is exhaustive. In the Philippines, He held a major show at the Museum of Philippine Art titled Hymn to Water; a major retrospective at the CCP, featuring a thousand artworks that was mounted in time for the IMF-World Bank meeting in Manila in 1976. The Sanso Festival, a 16-gallery exhibition, was held at the Artwalk of SM Megamall in 2002. Another landmark show titled Sanso: A Show of Shows, was held in 2009 at the Gateway Suites at the Araneta Center. Finally, a show establishing his Modernist origins, titled Sanso: Pioneer of Expressionism, was held at the Art Center of Megamall, also in 2009.

From the 1990s onward, Sanso started focusing on still life compositions as takeoff points for his poetic surrealism. Rather than dwell on the Black Period composition of solitary bouquets floating in the netherworld, Sanso liberated his floral compositions by first cleansing the air with a sharp tinge of pure coloration: the use of vivid light blues, greens, oranges, and aquamarines for background sky colors. This was mirrored with the use of globular vases and coral-like outgrowth of plant-like matter that allowed his still lifes to colonize newer, more dreamy terrain, like gigantic plants growing in a landscape. Among these are An Affinity of Dreams, which utilizes dramatic cactus-like forms (or perhaps enlarged versions of pendulous leaves of tropical orchids) that leans diagonally to the left, sprouting flame-red flowers, and backed by a cerulean blue sky. Another is A Fellowship Strengthened, wherein a cluster of red lily-like flowers gather in the center of a yellow-green combed flowerbed, like strangers meeting for the first time.

A slightly more abstracted version is Love Sonnets, where the blue-green textures of the flowers merges with the background texture of vase, table, and opposite wall, the whole contrasted by the flat crimson sky with its pale white moon. Among his more recent works are Tidings of Gladness, in which enormously drawn but tightly textured ovular vases that recall the classical forms of Roman glassware or Chinese porcelain become architectonic structures upon which rests an exuberant bloom of red flowers and green-yellow leaves.

Summer

In 2008, Sanso closed down his studio in Paris, and went home permanently to the Philippines. The move back to his Asian homeland after half a century of staying in Europe has also brought the artist full circle from the cosmopolitan bravado of Parisian Modernism to a different, more lyrical and heterogenous kind of Modernism found in the Philippines. Unlike the shattering paradigm shifts of Western Modernism that privileged the linear rise and occlusion of a series of privileged styles (i.e. Expressionism followed by Cubism followed by Non-Objectivism followed by Abstract Expressionism, etc.), Philippine Modernism has found that various aesthetic movements have clustered and coexisted within both the academy and the growing art scene for the past forty years: The Hard-Edged Abstractions of Lee Aguinaldo, Marciano Galang, Ben Maramag or Antonio Rambuyong has intermingled with the Conceptualism of Ray Albano and Bobby Chabet; the Minimalism of Philip Victor or Danny Garcia; the Post-Painterly Abstracts of Nestor Vinluan, Benjie Cabangis, Rock Drilon, Carlo Magno or Edwin Wilwayco; or even the Abstract Illusionism of Eghai Roxas with the same curatorial and commercial spaces of Pinoy Pop Art, Neo-Figurism, Social Realism, and neo-Folk Expressionism. What this implies is that the visual and aesthetic disposition of the Philippine artworld was much more diverse and compacted than the western art capitals like New York, London, Berlin, or Paris, where enough space could be found to distinguish these movements within separate spheres of influence—allowing monopolistic spheres of influence to be established at certain junctures.

Proof of this can be found in spaces as disparate as the galleries along the Artwalk in SM Megamall or at the Artspace in Glorietta, or the exhibition schedules at the Ayala Museum, Lopez Museum, Yuchengco Museum, CCP and the Metropolitan Museum of Manila, where the range of artworks shown are as diverse as traditional figurative pieces, abstractions, expressionist pieces, conceptual pieces, and post-expressionist works. As a result, for example, the dichotomic conflicts between “subject matter” and “form” have not been as cannibalistic as in the West that had resulted in the collapse or negation of other art movements. Rather, Filipino Modernists are forced to work side by side as the narrow economic and curatorial opportunities afforded in the Manila art scene equalized the chances for patronage or exposure. At another level of analysis, we can also observe that the restricted space for artistic production in Manila enforces a sometimes tense, sometimes amicable camaraderie among artists of different stylistic persuasions, and even coming often from the same academic backgrounds.

For Sanso, this heterogenous space of home is allied with a loyal collecting base whose enthusiasm allows him to produce stylistically diverse works. From his “poetic surrealist” phase in France, Sanso has started to return to more recognizable depictions of subject matter utilizing a more realistic representational drawing and painting technique derived from references in digital photography that he himself takes; while at the same time still focusing on highly non-representational forms like color abstracts that highlight a highly attuned sense of prismatic order and reproducibility using traditional media. There is a continuing thread in the artist’s experiments in color and patterns that could be seen as commencing from his late-1950s landscapes to his late-1960s textile designs, moving onward to his art photography from the 1970s and 1980s. Looking like crisp slides of color filters awash in darkroom chemist trays, his recent abstract works are revealed as painstakingly drawn and painted forms, which relies on a lifetime of experience in mentally calculating the precise patterns that result in pouring color washes on paper. These are then reinforced by expert layering of highlight and shadow paint elements, creating a three-dimensional effect akin to colored transparencies that are rumpled and sealed behind glass. Definitely continuing his experimental photography of the 1970s and 1980s, these highly abstracted works recall the best examples of Hyperrealist renditions of chemical reactions and kaleidoscope effects from a chromograph with its filters melting from the light intensity.

The first theme, however, reprises to the universal Sanso concern for scenes of beaches, coves, tidal pools, and rocky promontories, animated by sailboats and rowboats, serving as a recognizable icon for his Britanny scenes. These are often intermingled with views of luscious flora clinging to seaside bluffs; desolate windswept cliffs and mountainsides rendered in brilliant summer hues, and renditions of the majestic vistas of twilight set amidst sea and land. Unusually sharp and crisp compared to his soft-lit, romantically melodic poetic surrealism, the new works of Sanso looks as if one has awakened from a long dream, greeted by the bright sunlight of a summer morning near the beach filled with the brisk wind, the sound of waves crashing to the shore, and seagulls in the air.

Sanso’s modernist concerns were rekindled in his 2010 critically acclaimed show “Sanso Extraordinaire” held at Galerie Stephanie. The curators of that show culled rare works from Sanso’s Jade Set series, the Paintings within a Painting set and included some science fiction inspired landscapes and topping these off with the artist’s recent return in interest to abstract works. These refreshing visions of a timeless summer, which seems to catch Sanso at his most lyrical and figurative, are combined with his highly abstracted color series to reiterate Sanso’s biographical and art historical connection to Philippine Modernism, a reaffirmation of the vitality of the Modernist UP Fine Arts Batch of 1952, and his crucial membership in that elite confraternity of art masters. It is in his most recent exhibition titled Sanso Moderno with an initial collection shown at the newly-renovated Galerie Joaquin Main, at 371 P. Guevarra St., corner Montessori Lane, Addition Hills, San Juan del Monte City and a second set earmarked specially for the GJ Asianart Galerie in Singapore that Sanso goes full stream into his modernist realm. His starkly rendered landscapes, now rendered with more life through a dramatic sculpturing of forms from rocks, blades of grass, flowing waters, tree branches and leaves, and the sharp sky with its now solidly-blocked pattern of clouds using paint, resulting in a crisp rendition of the outdoors that continues the Modernist concerns for significant forms and patterns of color, arranged in oftentimes dramatic oppositions between complementaries and analogous patterns.

And yet, these works continue the poetic ardour for nature that can be felt from the artist’s landscapes from the late Fifties. These would include A Breeze Softly Serenades, a dramatic rendition of an inlet of the Brittany coast where powerful tides threaten to overwhelm a sailboat drifting over treacherous yellow sandstone shoals. Taken from a viewpoint high over the cove, the epic struggle to navigate through this mighty tide—a commentary of the microscopic significance of humanity in the face of overwhelming forces of nature—is shown almost as an afterthought, our attention riveted to the yellow-aqua opposition between land and sea. The only indication of danger are the foaming white crests of the waves that funnel in a diagonal upper right direction towards the shore, that leads the eye towards the solitary sailing ship caught between the heave of the sea and the crunch of the shore. Contrast this with As Calm Gently Sweeps, a more down-to-earth rendition of a sea cove with a gentle surf lapping upon its orange shores, another sailboat darting away among the feet of massive tumbling cliffs in the background. Here, serenity is signalled by the return of Sanso’s white sun, a solar body that brings heavenly light but not scorching heat. The gentle light source is embedded in the center of a brilliant cerulean sky of such intensity (heightened by salmon pink clouds) that one could imagine themselves standing on another planet. Emerald Tides puts this rendition unto the level of semi-abstraction, as the ceaseless struggle between pounding surf and unyielding outcrop results in feathery patterns that change ever-imperceptibly in the silent windswept shore.

As the Rush Approaches puts the classic Sanso vision of rocky shores in twilight to this re-rendered world where hyperrealistic color explodes from every stone and stream. Reminding one of the sharp color contrasts of heaven seen in the 1998 film What Dreams May Come, Sanso jettisons the warm colors of his orange or scarlet skies for cobalt blues and aquamarines, and reinvigorates his landscape with an uncommon understanding of a surreal vision shifted from the hyperactivity of oranges and reds towards the more visually restful blues and aquas. This recourse to blue as the predominant color of the series is repeated by In Endless Azure, a depiction of Sanso’s solitary rowboat beached in a cobalt blue estuary, the white sun casting no shadows in this summer dreamworld. Forest Trails deliberately contrasts the increasingly saturated color scheme with a black-and-white rendition of an upland forest, every leaf of every branch miraculously rendered in detail with the patient sagacity of an eighty-one year old master.

In turns both enlivening and inspiring, Sanso Moderno thus shows the endlessly vital spirit of Juvenal Sanso as he rightfully claims the mantle of senior master, a model of artistic integrity to Modernist innovation and progression that infuses Filipino culture with the best of global aesthetics, reworking both local and international into a dreamworld where the eternal voice of summer is always riding in the breezy sunlight.

Notes:

1Alfredo Roces. Sanso. Manila: Luis Ma. Araneta, Filcapital Development Corporation, and General Bank and Trust Company, 1976, pp. 90-91.

2Emmanuel Torres. The Chronicle Magazine (May 7, 1966), pp. 22-25. In Alicia Coseteng, ed., Philippine Modern Art and Its Critics. Quezon City: Unesco National Commission of the Philippines, 1972, pp. 104-105.

3Reuben Ramas Cañete. “Sanso’s Homecoming,” The Philippine Star, December 21, 2002, Modern Living Section, pp. G1-G3.

About the Author

Reuben Ramas Cañete, Ph.D is currently Associate Professor at the Department of Art Studies, the University of the Philippines Diliman. He received a Bachelor of fine Arts in Painting from the University of Santo Tomas and an M.A. in Art History and Ph.D in Philippine Studies from UP Diliman. A writer, art historian, teacher and independent curator, he has contributed to Many local and international publications and authored books on the field of Philippine art and culture.