The Unencumbered Spirit

The sculptor Allison Wong-David has long been drawn to nature as a major theme in her sculpture and installations. Where there was once a controlling hand at the heart of her oeuvre, there is now a freer line and a belief that there is great beauty to be found in imperfection.

By Ian Findlay

Seventy kilometers south of Manila, at the entrance to Lipa City, in the province of Batangas, the Hong Kong-Filipina sculptor and installation artist Allison Wong-David has her spacious studio. Here, numerous finished works are waiting to be moved and a number in progress wait to be completed. There is a sense of careful placement of the works around the two-story studio. The farm in which it sits mirrors many of the studio’s chance arrangements. This idyllic location provides bucolic solace for the artist far from Manila’s cacophonic bustle. Here fowl, goats, and dogs wander through the trees and around the grounds, carefully avoiding the farm’s well-tended vegetable and herb patches. Such activity helps subliminally to focus Wong-David’s attention as she shapes her plywood, stainless steel, paper, and clay into the dignity of sculpture.

Wong-David has considered many subjects and themes in her art made over the past three decades. As she has developed her aesthetic away from Western notions of realizing sculpture, she has come more and more to attain a freedom of thinking and making that have their roots in the Japanese notion of wabi sabi, an aesthetic concept that accepts imperfection and embraces it.

Working in her studio on her farm it is easy to understand Wong-David’s attraction to nature generally and landscape in particular as major themes in her art. One sees a more relaxed artist at work today that just a decade ago.

“I have become very ‘wabi sabi’ in my art-making. I have become freer in my work and in my awareness of what is beneath the surface of that which I see around me,” says Wong-David. “My aesthetic is more layered than a decade ago. Now I find beauty in imperfection. Nature shows us that it is okay to be imperfect.”

One senses this freedom in her pit-fired stoneware piece entitled Marcy (2008–2009). The seemingly random stoneware pieces, like those in another work of the same time called Seeds (2009– 2010), are really carefully arranged. Much thought had gone in the making of the individual pieces. There is a sense that an archaeological dig has taken place and an ancient shattered collection of “bones” has been revealed. Standing back a little from this work one sees a broken face, “Marcy” staring back at one. There is imperfection here but there is also an inexplicable serendipitous perfection for us to enjoy. Within this work, too, one becomes deeply aware of the extraordinary images that the earth throws up over time, fragmented landscapes from the bowels of the earth that make one think of infinite time.

Landscape is, of course, not one thing, not an island alone, not one essential aesthetic,

not a definitive vision of nature itself, not only trees and clouds and rivers and sky. Landscape for Wong-David is a wonderful treasure trove of inspirations that will become exceptional sculpted works.

As Wong-David says: “The one thing, the best thing, that I can say about landscape, is that it is fluid, ever changing.” And another aspect of the fleeting in nature that she has tried to capture in her work and always fascinates her, as it did John Constable (1776 –1837), are clouds. For Wong-David clouds “represent the ephemerality or the transience of our reality. I can really understand why both Constable and Turner were mesmerized by cloud formations. These are forms that are never repeated.”

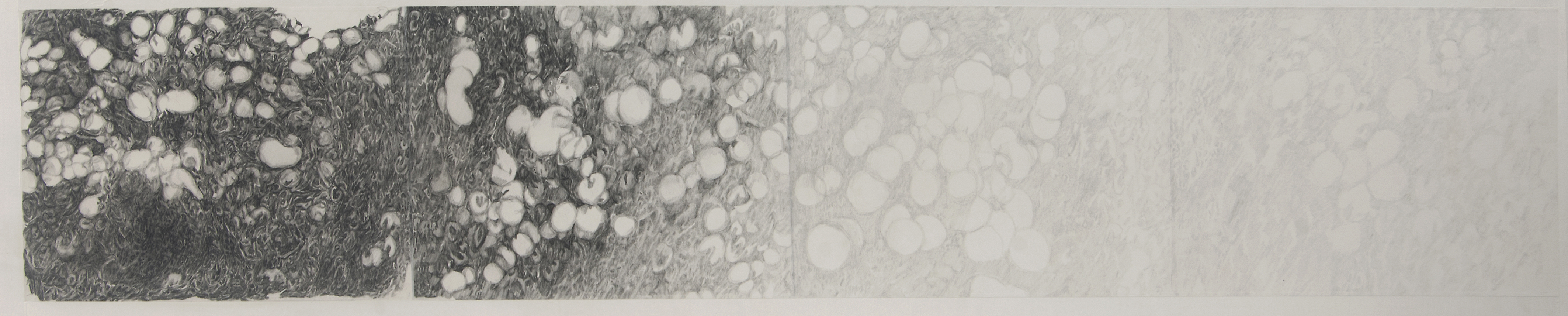

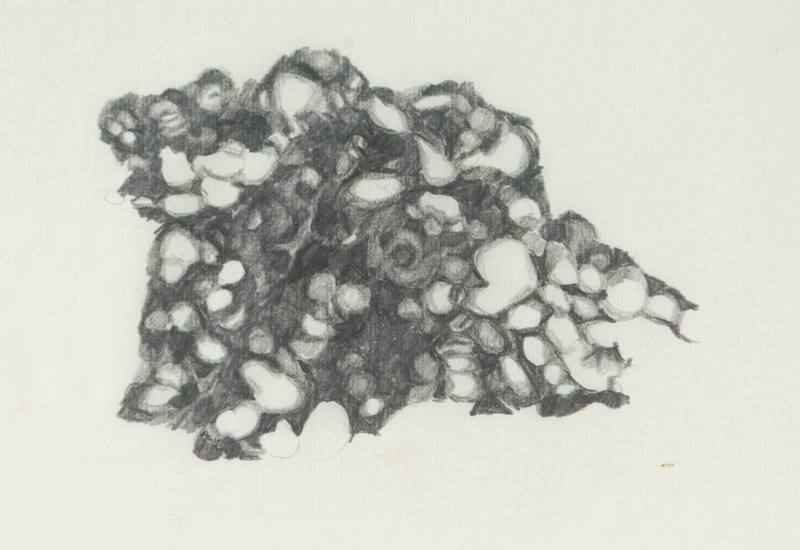

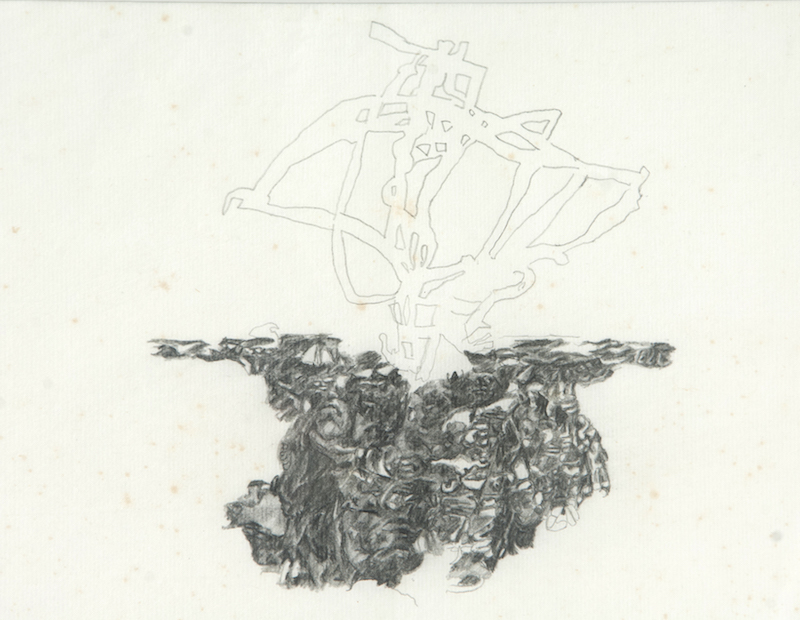

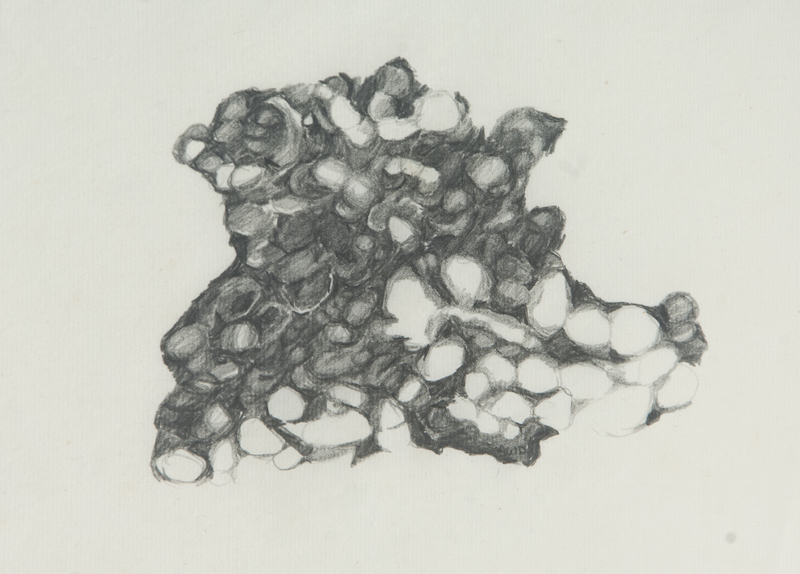

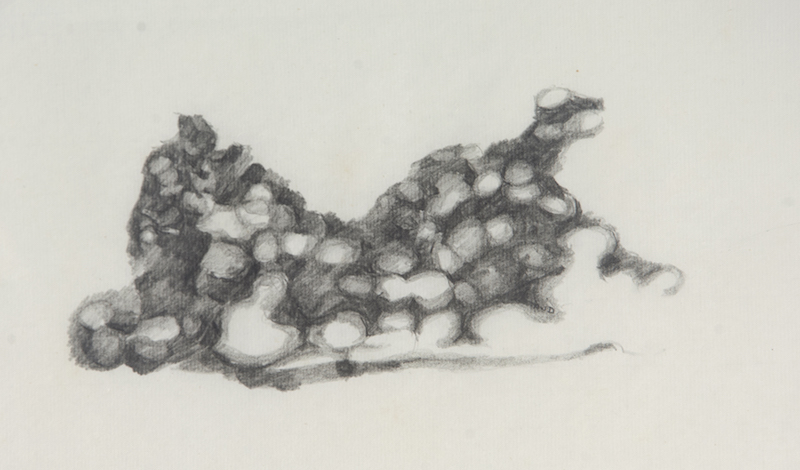

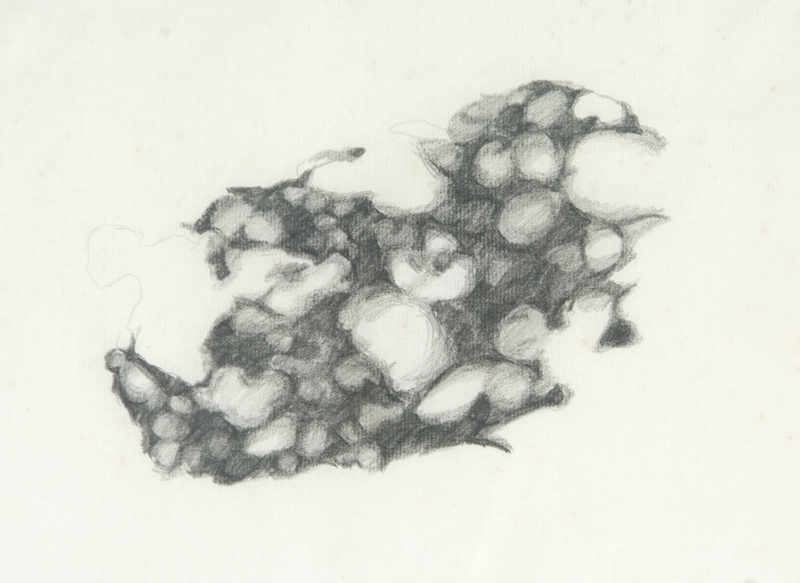

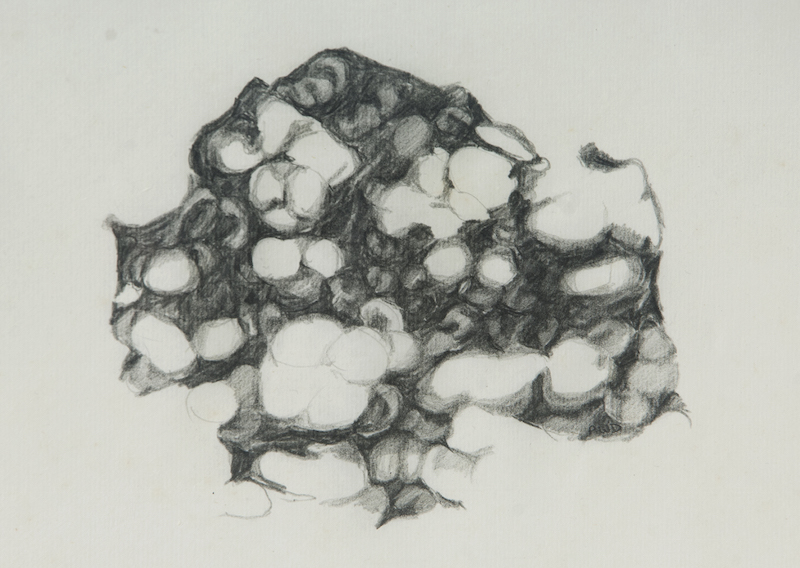

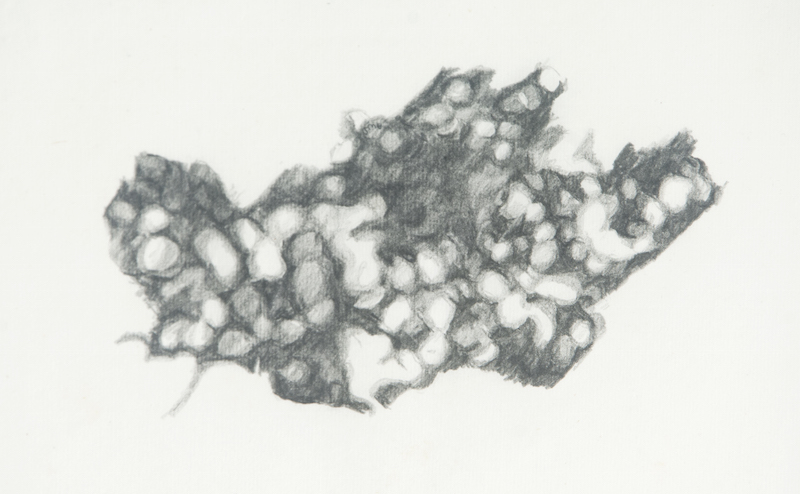

Wong-David’s approach to beginning her exploration of sculpted landscapes through boxes is very different from that of most other sculptors and painters. Her pencil-on-Chinese rice-paper drawings for her on-going series of boxes under the title Ether are of clusters of twigs and branches, and yet for all the density of these drawings there is a feeling that they are breathing entities. These drawings—along with the other contents of Ether series boxes such as Box 1, 2, and 9 (all 2015), including wood, cardboard, Chinese rice paper, photographs, pencil, stainless steel, stoneware pottery, and twigs—serve as beginnings of larger ideas. While these box works are small, they are not studies but complete works. These small works are also micro worlds in which Wong- David’s notions of wabi sabi are also at full play.

The Ether series of boxes may also be viewed as small ‘books’ revealing the world of nature. These are intimate expressions of nature’s varied aspects to which Wong-David is attracted. But she finds intimacy beyond the confines of the box, too.

This sense of intimacy is expanded upon in a surprising way in a work that represents a group of clouds, made of more than 100 stainless-steel pentagons. The movement of this work and the reflected light of this suspended sculpture speaks to the impermanence of the nature’s moments, for clouds are but moments, diverse and always different. When I first encountered this work, I was reminded of Alexander Calder’s mobiles and how the toughness of sculpture can reveal the most fragile realities of nature to us.

In 1980, Allison Wong-David went to the Slade School of Art but graduated from Chelsea Art School in 1983. When talking with her about this time, one senses that the enthusiasm of her art college years remains within her. She notes that, when she began sculpting, there wasn’t anything in particular that she wanted to achieve. Even now, as she explores the personal and the objective worlds, one senses that the only ambition she has is to make art that will connect to others beyond her own world.

As she says, “I didn’t have a particular message or anything I wanted to say, just as today. I wanted to make things. I realized that making sculpture was a way of discovering the world and myself. I don’t think I have ever been trying to say anything particular in work. I really want my work to tell me something about myself and about things that I don’t necessarily see. My art basically has taught me about life, something deeper than primal feelings.”

The need to free her spirit of discovery and of exploration has been vital to the success of her object-making. This deep desire permeates many of Wong- David’s large works but is, perhaps, most clearly seen in her uncommonly elegant collective stoneware sculpture/installation entitled Duende Village (see the Cover) that occupies a small grove adjacent to her studio. On seeing this work one comes to understand another layer of meaning in Wong-David’s expression of wabi sabi.

Duende Village, begun in 2011, continues to develop. The duende (spirits or goblin-like creatures) are of various sizes, and represent upturned root forms. They are fired for three days in Wong-David’s two-chamber anagama wood kiln, which took three months to install. As they are large hollow works that need to be made in parts, she uses a coil extractor to remove clay. When the works are removed from the kiln, they are forever changed: one can sense something of the spirit of the clay that suffuses our imaginations with a sense of earth’s mysteries.

Throughout her career Wong- David has used varied media. She has combined the likes of painting, stainless steel, wax encaustic, pottery, plywood, canvas, drawing, stone, and copper to make vibrant art that addresses her rich cultural influences: Chinese, Western, and Filipino. Her choice of media informs not only her forms but also the colors and textures of her objects. “The material,” she says, “is a means to an end. I don’t have a favorite medium or have any preconceived notions of what the materials can do for me. Even though I do plan how to use my materials, I work more from instinct now than ever before. I am not afraid to change my mind. So I trust myself more. And one thing that I have found in recent years is that I am less controlling with my materials. I am so much freer now. And my work talks to me more. This has surprised me and it gets me excited.”

Her sense of excitement is seen in the interaction of forms that suggest an artist who is interested in a number of genres, from writing to calligraphy, and from photography to painting, and to the majesty of the natural order from the ephemerality of clouds to the rugged constancy of earth. This is beautifully realized in a number of her drawings for her boxes in Ether series where the written and pencil-drawn figures provide a gentle counterpart to her porcelain and stoneware pieces in the boxes. Photographs also play a small part here.

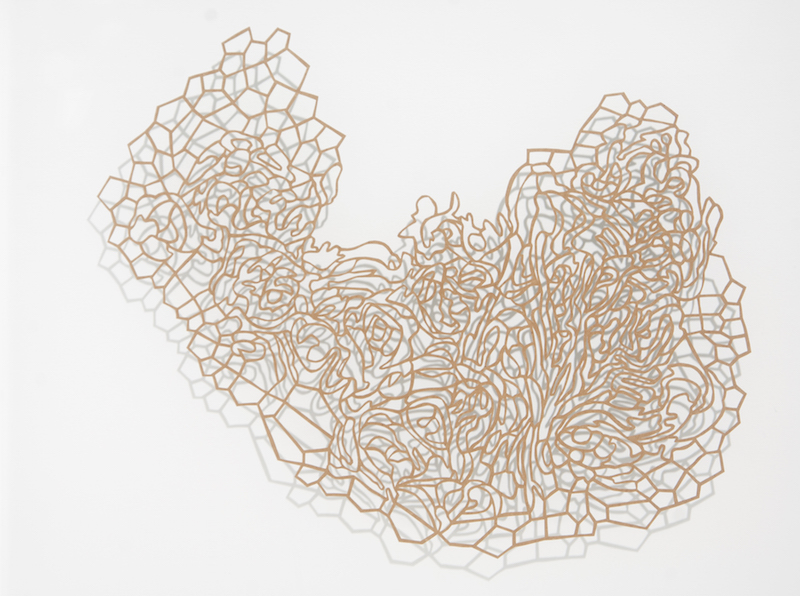

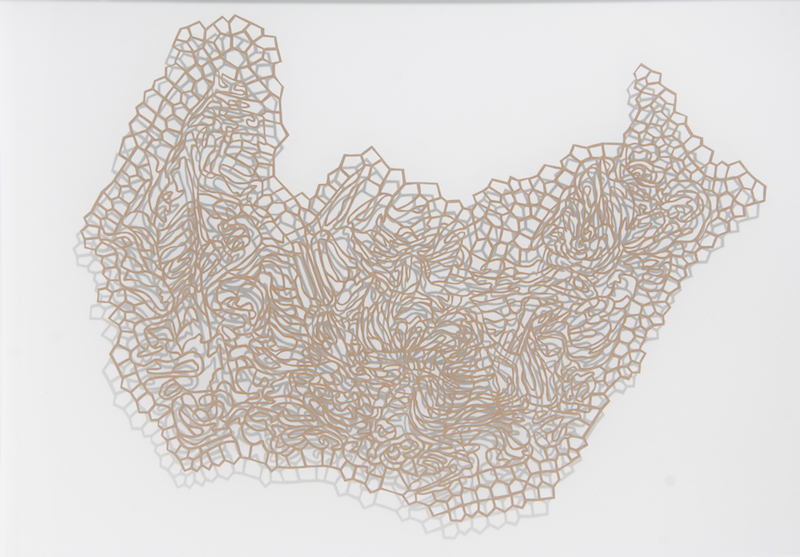

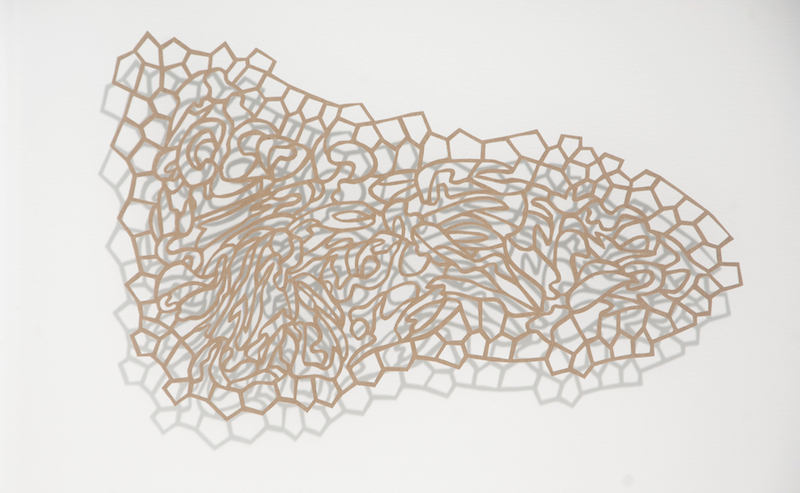

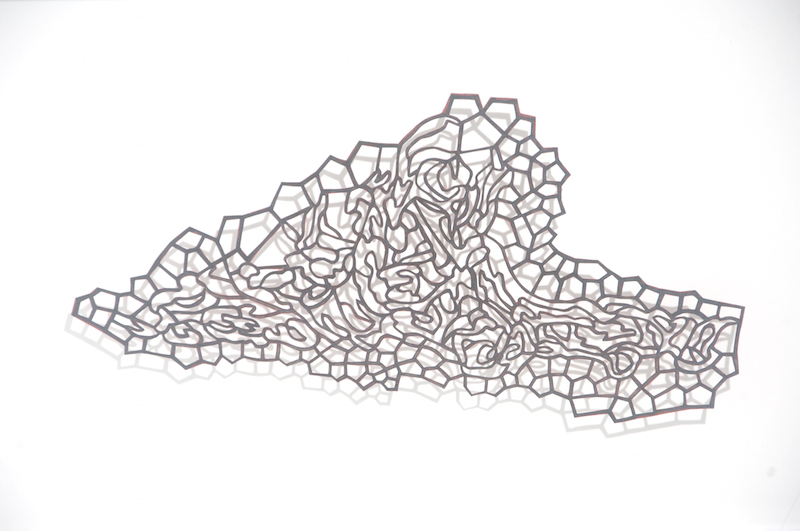

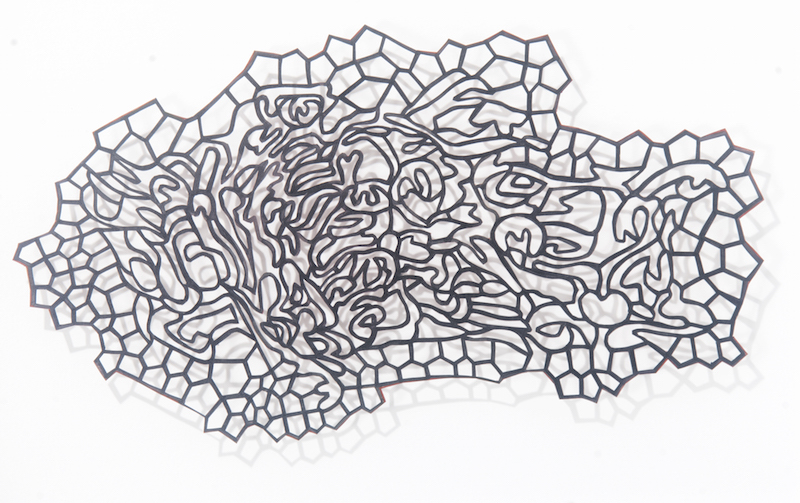

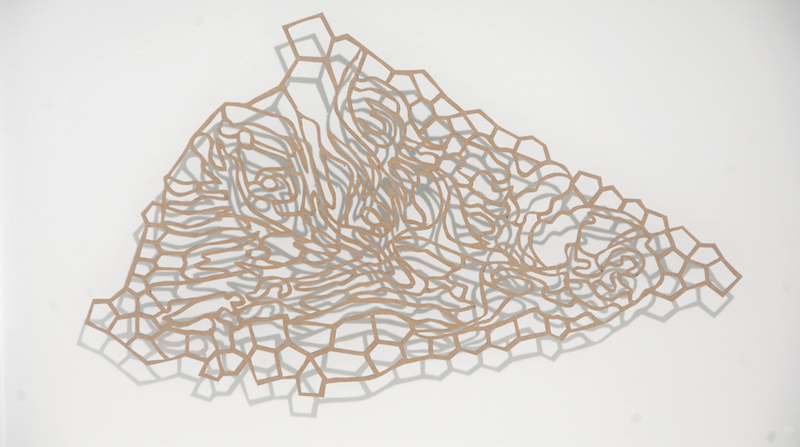

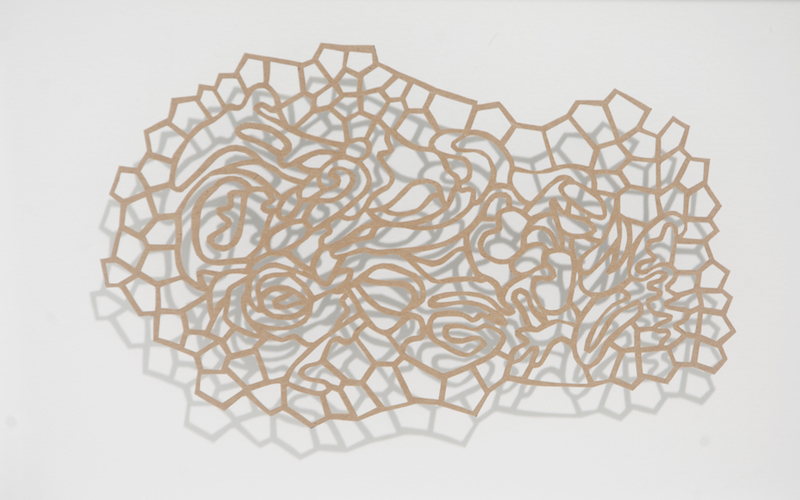

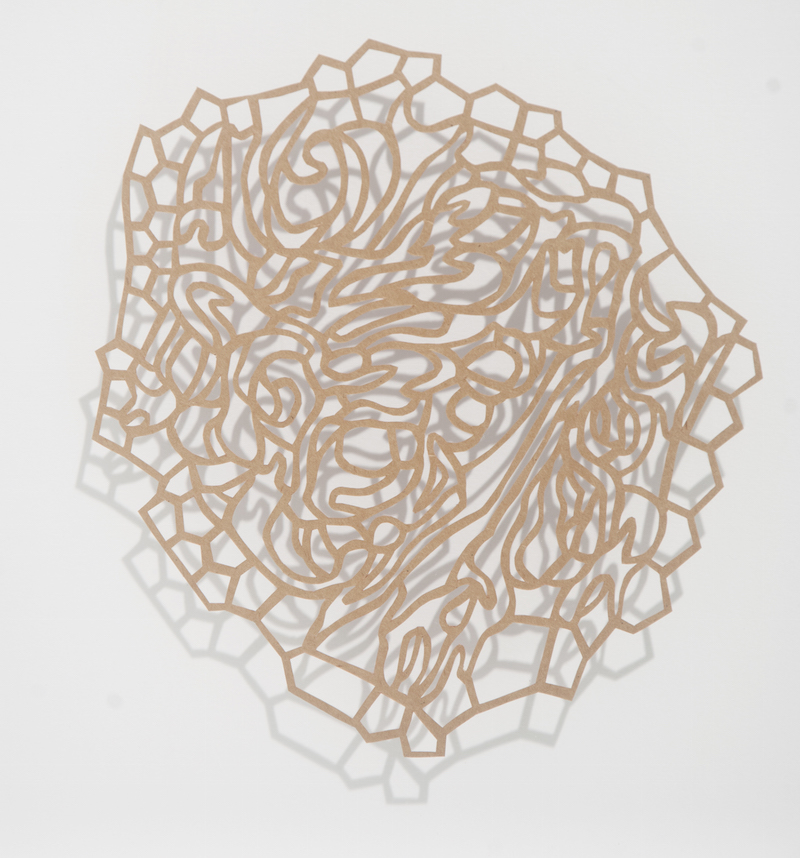

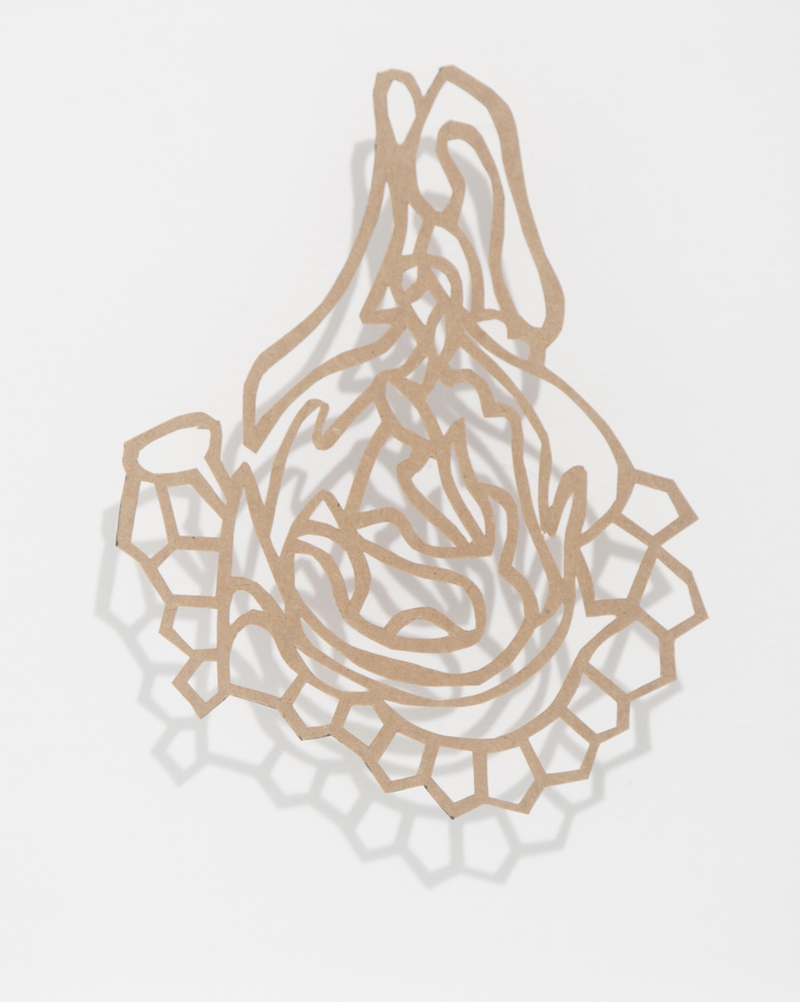

One is aware of a number of natural elements in Wong- David’s canvas-and-wooden Shield series (2015). These painted pieces suggest small landscapes, but in their lightness one might easily imagine them to be multicolored clouds. Calligraphy and painting are also suggested in the singular floor piece entitled Unrooted (ongoing since 2011), which is plywood over a wooden frame. This work suggests a calligraphic influence to me, but Wong-David notes that its origins also lie in Chinese painting. As she notes, “These are 3-D representations of painting brushstrokes.” There is something quite tantalizing about this form or ‘brushstrokes”—the various parts also suggest a group of animals slithering on the floor.”

The sense of violent natural drama is found in Wong-David’s recent Ether collection of dodecahedron atop mango trees and their roots, torn from the ground during one of the Philippines’s frequent typhoons. Atop each severed truck is a regular 12-sided dodecahedron. The works in this series, which are made of fallen mango trunks, stoneware, porcelain, and stainless steel, have an energy to them, unusual in Wong-David’s oeuvre.

The earlier Solid Rock (2009) (plywood over a wooden frame) suggests her beautifully realized Memories (2009), which was made of shiny stoneware slabs on a metal frame. Although using very different materials, both of these works recall a primordial past in which life emerged struggling to survive. There is something primal, too, about Wong-David’s Self-Portrait (2006). The self-portrait is more about the fragmenting landscape

than that of humanity.

At the core of Allison’s Wong-David’s art is the survival of life and how we control it. Her art then speaks boldly to the intensity and fecundity of the natural world as befits that of an exceptional artist. Her art also consistently engages our imaginations with the “beauty in imperfection” as well as humanity’s place within it.