Linked together in their bent toward the child-like, Roby Dwi Antono and Keiko Yokoyama make for an unlikely, albeit wondrous, pairing.

Keiko Yokoyama’s works transport one back to the innocence of childhood. But what makes Yokoyama’s approach in her narratives so distinctly clever is that the artist does not apply a nostalgic patina to her works, despite their vintage treatment. Such is the reason why the works arouse a sense of child-like awe and wonder, rather than melancholy, as it communicates in tandem that these experiences were never ours to possess. It is as if there is a deep reverence by which these candid moments are made inviolate; expectation is leveled to receive these glimpses thoughtfully. Like a gift.

The radiant work Spilled Milk is generous in this regard. In the well-lighted kitchen, the action is between a toy bunny and a toppled cup; the child, perhaps saddled with newfound guilt, perhaps consoled already, is missing. The perspective is amusing: Here is a life free of want, right as attention spreads across the shelves’ ample stocks. The marvel in Vintage dog plush toy is the bond struck between the subject and viewer: that the toy seems remarkably alive is a discovery made by one who had just recently learned to crawl. Harmony in this warm abode is at its most simplistic in another work, where a quarter note depicting the musical scale’s perfect fifth (what sounds the “pop”) curiously propels a child off her tiny feet. Cadence — the capacity to be in step with one’s surroundings, to be whole with them, is what envelops the child’s first experiences.

This ‘Zen’ sensibility of being in accord with nature is an abiding one, through which even one’s fantasies align. In one painting, a child dressed as a butterfly looks back at us in wonder, untroubled as an outsized bee draws out nectar. Teddy bears, as much as angels, can make for warm company, as can a wooden toy elephant, who had turned its head to check if the child straddling its back is ready to take flight. Still, the most delightful encounters to be had in the works of Keiko Yokoyama are premised on her gentle touch. What makes Yokoyama’s child-like narratives so enchanting are her minor tweaks — the odd angle, the one suggestive detail — as though in keeping with the idea that most vagaries of life come from any greater imposition. It is perhaps for this reason that depicted in Spilled Milk, too — and recalling the idiom — are the readily available comforts: morning, breakfast.

Could it be that all have such an indivisible right to a peaceful life? The works presented here appear as much as Yokoyama’s tacit nudge toward presence of mind as they do as a contrasting device, between innocence and, differentially, the adult experiences that may say otherwise. But it is precisely in her charming form of engagement Yokoyama endows us with that inverts this dichotomy, in turn presenting a golden truth: that what defines or muddles the two is the mindfulness by which one responds. It is a hallmark of an artist that can have us believe, even for a moment, that it is truly that simple.

But where Yokoyama presents the child-like in fixed, untroubled states, the works of Roby Dwi Antono are more like victuals for the eye, which, in their delectable palettes, smuggle in a notion of childhood as a time for oddity and uncanny transition, a period of wayward exploration of a nascent psyche’s inner world. As such, singular focus on subject is a distinctive trait in Antono’s works.

Interestingly, the Saturday morning cartoons, films, and television series of his youth left a remarkable imprint on the famous Indo pop surrealist. Of note to Antono are the kaiju and Urutora kaiju of the Godzilla and Ultraman franchises, giant monsters often conjured up by joining different parts of known species to form almost untraceable, composite wholes. It is perhaps for this reason that Antono’s characters are distinct in that they appear more like changelings, charming as they are unpredictable.

Meanwhile, it is pertinent to note the kaiju genre historically. It had long been considered a reflection of Japan’s complex postwar psyche, as early back as the first Godzilla’s 1954 premiere. Premised on the idea of a colossal “terrible-monster” who rose from the sea to lay waste on cities, the kaiju served as a fitting metaphor to bypass nationwide censorship in addressing the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, which the Japanese government had at the time unequivocally banned. Cool Japan — the nation’s overall branding strategy of its culture post-economic recession — was an initiative that begun in 1980, but it was only through a survey in 2002 by Douglas McGray for Foreign Policy that recognized its success as a soft power for its massive cultural influence. A plethora of Japanese popular culture earmarked this time and not least of which anime, which appeared as much in the west as it did in countries of interest, such as ours, the Philippines, and our neighbors — Indonesia, Antono’s homeland — as they occupied television prime times in the 1990s. Coincident in this time were the beginnings of the Superflat movement led by Takashi Murakami, the compositional aesthetics of which shaped a lasting image of Japanese visual culture as it pounced on the global limelight.

Such history may illuminate how Antono’s continuing investigations of his past and how such causes inflect present esoteric states of mind remain as relatable as ever, kept tastefully recondite through his surreal scenarios. It’s also a wellspring of material: as his signature style is housed in the Pop Surrealist tradition, the genre remains fruitful in its famous capacity to mine the unconscious and ably link seemingly disparate images to startling — and, in hindsight, entirely sensible — effects. The artistic merit is as much founded on Antono’s skill as it is in his facility to “tap” into the collective mind. Likewise, just as Yoshitomo Nara, one of Antono’s oft-cited influences, captured the anti-establishment spirit of his time through images of girls brimming with spite, girls who never quite ‘grew up,’ perhaps what has so many identify and connect with Antono’s characters is their outwardly strange yet irreducible physiologies, reflective as much of the uncertainty of the present times as they are of the multidirectional impact of the pop culture we grew up with and had.

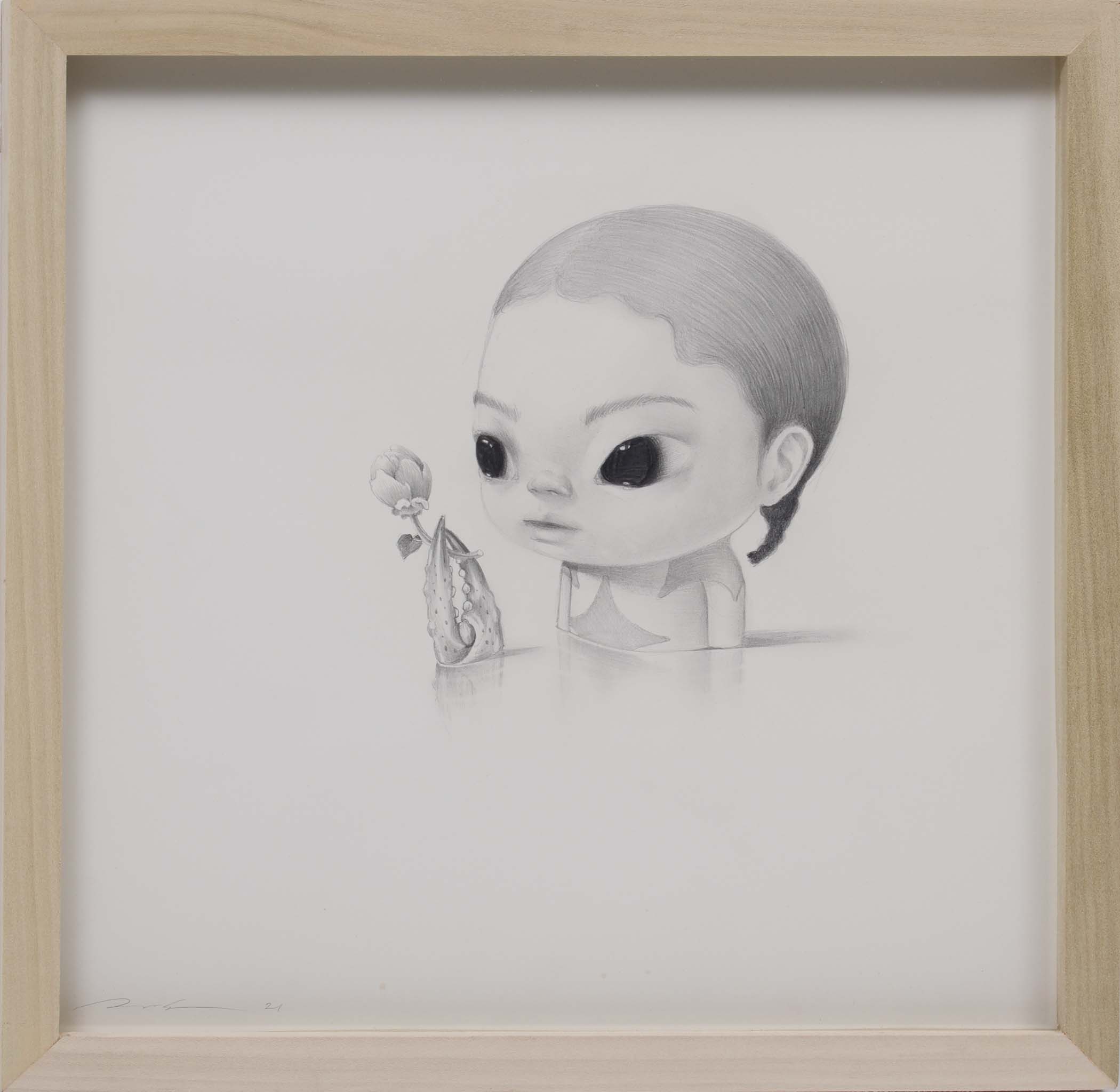

Nonetheless, one need only look at the eyes of Antono’s characters to arrive at similar ideas of identity and change. Reversing the common expression that the eyes are “windows to one’s soul”, the eyes Antono’s characters possess give no quarter. They are remarkably opaque, and in the case of the monochrome works Rin, Claire, and Amy particularly, seem to be increasingly fogged and cloudy the further they dilate. Bulging and with remarkable convexity, these eyes seem able to apprehend full panoramas at an instant, with thought lagging behind the bodies processing it all. There’s certainly something about the children, nowadays.

—

Between the Untroubled and Uncanny: Keiko Yokoyama and Roby Dwi Antono

exhibition notes by Jose Naval

curated by Ricky Francisco

—